CHAD: A semblance of education for a displaced child

Sitting on a plastic mat in an outdoor classroom at a site for people displaced by violence outside the town of Goz Beida in southeastern Chad, Ibrahim Abdoulaye Moussa has reason to pay attention in class.

"I'm in school to save my country," said the boy who is one of 180,000 displaced Chadians scattered around the vast semi-desert east of the country. "I dream of being president."

Before, in his home village of Djédidé along the border with Sudan, the closest school was a three-hour walk. Only after he and his family arrived at this site was he able to go to school for the first time.

At 14 years old he is now in Grade 2 of primary school.

Over the last year and a half, the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF) and some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have begun building an education system for Chadian children displaced by inter-communal fighting and cross-border attacks by Sudanese militias.

The challenge is enormous. Enrolment rates for school-age children were less than 10 percent even before the violence began so the agencies are almost starting from scratch. There is little infrastructure, few teachers, and limited interest in education from the government or the international community.

"Me, Sir! Me, Sir!"

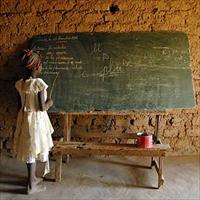

At the Gassiré site for displaced people outside Goz Beida, all 200 children in a makeshift classroom are raising their hands, eager to give their teacher Mahamat Abdelkarim the correct answer. He has written the letter "O" on the blackboard and is asking them if they know how to pronounce it.

Abdelkarim is a community teacher, a rare commodity in eastern Chad, Andrea Berther, UNICEF education programme officer, told IRIN.

"The biggest challenge is the lack of teachers," she said

Illiteracy in Chad's east is estimated to be between 90 and 95 percent, she added. Finding local people to train as teachers who can read and write is difficult.

The few that are found usually come with a First Grade education, and often they can earn more money working for NGOs, Berther said.

The question IRIN asked the few teachers here sitting on mats under sticks and plastic sheeting is, why do they stick around?

"These children are our children," said Baharadin Anour, a community teacher who was recruited from among the displaced at the Gassiré site. “We cannot leave them without any education”. He himself was given just 10 days of training in order to become a teacher.

The state

The state does send some salaried, trained teachers to the east but many leave due to the harsh conditions and insecurity. For the 2005-2006 school year there were just 37 trained teachers for 104 primary schools.

But even harder than finding teachers is finding money to pay them.

"It's deadlocked," wrote Namia Doumbaye, Ministry of Education delegate for the Dar Sila department. "The answer lies in community teachers, [but currently] they are ill-trained and [often] refuse to work because they are mistreated financially," he wrote in his 2006 end of year report.

The government pays community teachers about 30,000 CFA francs (US$67) per month though it takes on very few, said Elise Joisel, the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS)'s director of education at Goz Beida. “They have very small quotas," she said.

Instead, JRS has begun paying the bulk of community teachers' salaries, plus parents from the communities chip in.

Quality

From behind the plastic sheet that serves as a wall for one of the outdoor classrooms at Gassiré comes the sound of a child being whipped.

A few metres away, neither the JRS director nor the UNICEF representative seemed very surprised. "We try to raise awareness," Joisel told IRIN. "We tell them [corporal punishment] is not allowed. But it's difficult."

She said bringing students into the classrooms was a first step. The second is going to have to be improving the quality of teachers.

Parents

But even with teachers, makeshift classrooms and a school feeding programme many children are absent.

"The majority [of parents] do not know the importance of school," said Zakaria Ousman, president of the parents association at Gassiré’s school.

Children, and particularly young girls, in displaced families often spend their days walking or on donkeys, searching for wood they can sell – one of the few forms of revenue for the displaced.

School books distributed to children at school are found on sale in Goz Beida's main market.

"In Chad, the understanding and the demand for education at the community level is very poor," said Katy Attfield, former country director of the NGO Save the Children UK. "We're trying to provide the teachers and the schools so that the supply is there, but… creating the demand for education is the bigger work.

Schools

There are areas in the east where education barely exists. A three-classroom school in the small town of Adé, along the Sudanese border, has not officially opened its doors in two years. Informally a community teacher teaches a group of 28 students what little French he knows.

At a nearby site for displaced people, Youssouf Cherif has turned his straw home into a makeshift classroom, using cardboard as a blackboard and branches as improvised benches.

"Since we've been here, there isn't one child who has gone to [a real] school," he told IRIN.

New schools

Yet there are areas in the east where access to education, instead of decreasing with the violence, has actually increased. In fact the number of children in school shot up 15 percent in the department of Dar Sila which is where most of the displaced populations in the east live.

"[Before when people were living] in remote zones, no one saw to education," Hissein Djaba, a UNICEF education officer, told IRIN. "[Now], through the grouping of schools in the sites for [displaced people], children have the chance to go to school."

Still the agencies providing education are working on a shoestring. Of the $287 million the UN and NGOs requested for all humanitarian operations in Chad for 2008 only $15 million was requested for education. And while donors funded 97 percent of the overall appeal they gave only 12 percent of the amount requested for education.

"It shows that education doesn't have a very high place on the scale if you compare it with the other sectors,” said UNICEF's Berther. "It is important to make clear that in the humanitarian sector, there is a need for education."

According to Education Ministry delegate Doumbaye, the Chadian government’s priority for education is even lower.

"We have no suggestions to make because none of our suggestions have ever been taken into account,” he stated in his government report on education. “We beg the Good Lord that our situation improves."

Back and Next - Back and Next

Back and Next - Back and Next See Also - See Also

See Also - See Also